How Deep Is the Dangerous Water?

Estimating the depth of the silent banking crisis

If you’ve ever been around whitewater, you know one of its greatest dangers is the unknown. Its opacity could hide shallowness or untold fathoms—or anything in between. When we look at the banking sector today, there’s whitewater everywhere.

Our very first newsletter explained why the banking crisis that reared its head in March 2023 was still very much alive six months later. Now, we’re sticking our heads into the whitewater to give you a sense of how deep the crisis really is.

First off, every bank is insolvent. That’s not something unique to the post-SVB world or even the post-covid world of unprecedented money printing by the Federal Reserve.

Instead, it’s a function of fractional reserve banking. When you put money on deposit at a bank, the money is lent out, but still remains available for you to withdraw. It is Schrodinger’s Dollar—simultaneously a deposit asset for you and a cash asset for someone else.

That’s how the banking system creates money, and it also means that if all depositors ask for their money back, the bank will be unable to fulfil its legal obligation. It’ll have to break its contract with all except the first 5 or 10 percent of depositors.

Thus, as a bank levers up, it creates risk not only for the shareholders but for depositors as well.

In assessing the disposition of banks, therefore, we need to consider that a clean bill of health is not possible in today’s monetary regime. A patient who is anything other than terminally ill gets a passing grade.

Currently, banks are sitting on what appear to be adequate stockpiles of cash. Neither small nor large banks are liquidity constrained, as seen from their ratios of cash to balance sheet size.

Likewise, banks also appear to have sufficient cash to meet normal deposit demand, so there’s no fear of an imminent run. Even if they come up short, there’s always the discount window at the Fed as well as plenty of T-bills on their balance sheets that can be sold at par.

But that’s where the good news ends. As far as the cash situation goes, two things are currently making the situation look better than it is.

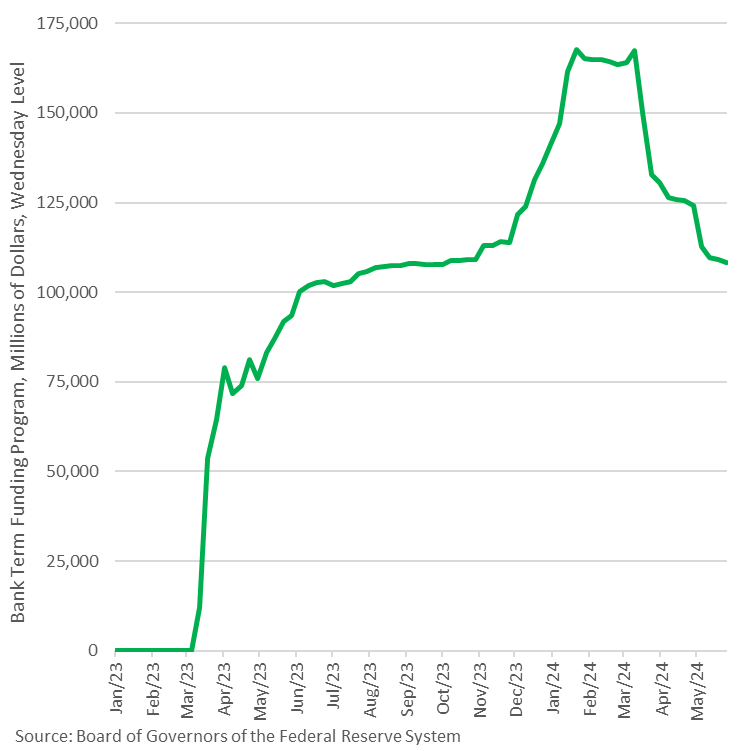

Banks still have plenty of cash from the Bank Term Funding Program facility, over $100 billion worth. But all of that will disappear by mid-March 2025, when the last of those loans come due.

This was never a permanent solution, as Powell & Co. were always making it up on the fly. Their attitude of shoot-ready-aim also turned the BTFP into an arbitrage opportunity for big banks, creating a massive and unnecessary cash infusion into the system, to the players who didn’t need it.

Ending the arbitrage doomed small banks and even the large regionals, basically anyone who actually needed the facility. Once again, it was shoot-ready-aim at the Fed.

Then there’s also the faulty seasonal adjustments inflating the cash position of small banks, but that’s a mathematical fluke that will resolve itself as the year goes on. What goes up, must come down.

But what won’t resolve itself is the underlying cash shortage nor the liability side of the ledger.

The basic problem at many banks is still an interest rate mismatch where they have relatively high-rate liabilities (deposits) paired with low-rate assets (loans).

You can lessen that problem by levering up and making more dollars in loans per dollar of deposit, and plenty of banks have already pursued this riskier strategy. Of course, when depositors want their money back, you’ve got a problem.

Being that overleveraged makes you susceptible not only to anomalies like bank runs, but also to more common shocks, like unusual demand from depositors.

When you’re 20 times as leveraged, a small disturbance becomes a catastrophe. A pothole at 5mph is a crater at 100mph. 20 times the leverage, 20 times the speed.

Similarly, losses that you might be able to absorb quite easily when not levered up are enough to completely sink your ship when overleveraged. The fabled hedge fund Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) was leveraged 250-to-1 when seemingly insignificant financial disturbances brought wrecked the fund.

Enter commercial real estate, stage right. Not only do small banks hold more of this toxic asset class in relative terms according to the size of their balance sheets, but they also hold more in absolute terms too.

It constitutes nearly a third of their assets. And the subsector is falling apart. There are fire sales all over the country as owners go bankrupt and walk away from their properties. Valuations are way down. Leases aren’t renewing. Hundreds of billions of dollars in mortgages are coming due this year with no way to affordably renew them.

To sum up, banks don’t really have anywhere near as much cash as they say they do. Their other assets aren’t worth anywhere near the face value anymore. And they’re overleveraged.

But just how bad is the banking sector situation right now in terms of dollars? Well, it’ll take a lot less room if we use larger units.