Jerome Turned On the Printer and Nobody Noticed

The Bank Term Funding Program Just Got Silently Supercharged

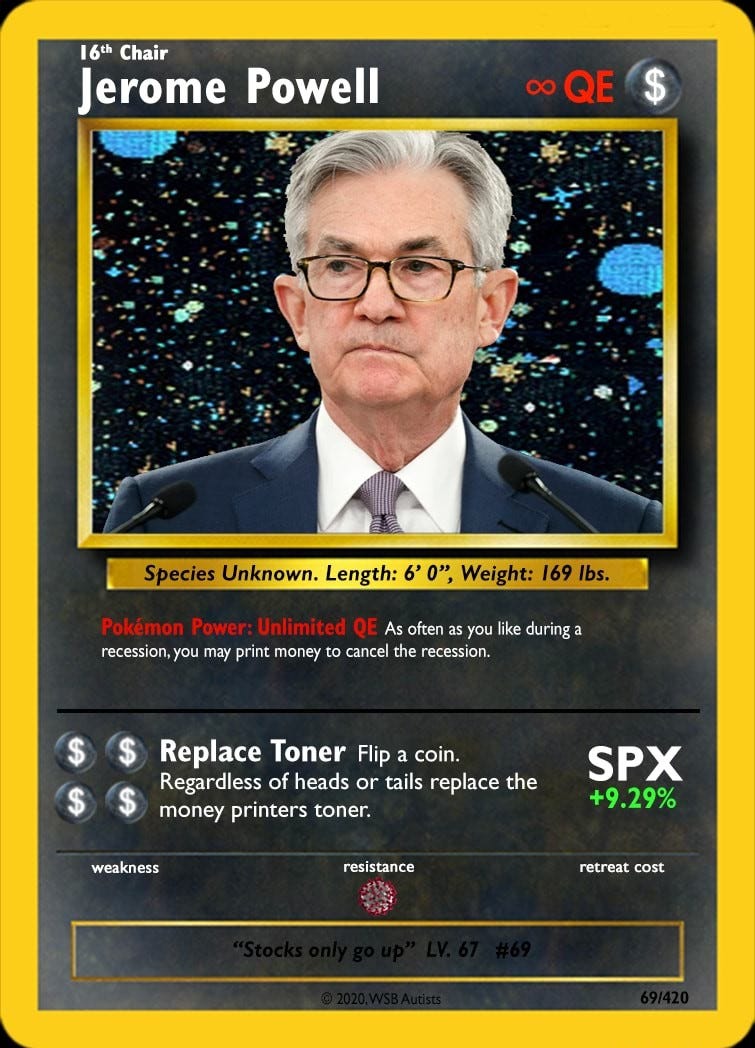

Powell & Co. are constantly finding new ways to inject liquidity into an economy running on fumes. This time, they’ve juiced the Bank Term Funding Program, effectively sweetening the deal a bank can get on these emergency loans.

The Fed is offering loans at rates below what it pays to banks who park money in its vaults. A financial institution can theoretically borrow from the Fed at 4.94% as of Friday, January 5, and then earn interest on that money from the same Fed at 5.40%.

At first glance, that sounds like the secret to alchemy, and one wonders why every bank is not storming the BTFP to convert every last asset they own into fresh cash that they can turn into bank reserves.

Is the recent surge in borrowing from the BTFP merely this magical arbitrage that Wall Street is taking advantage of at our expense? Yes, in theory - but not exactly in practice. It’s significant, but not an immediately earth-shattering change.

To understand why, we first need a brief overview of the BTFP’s mechanics.

It lets banks take loans while posting devalued assets as collateral. The Fed created this facade of normalcy to paper over the massive interest rate risk they created by forcing interest rates to zero and then promising rates would stay there for years.

Promise made, promise broken.

When rates rose, banks found themselves loaded down with fixed rate loans at low interest rates (think 30-year mortgage at fixed 2.125%), but liabilities at variable rates which quickly exceeded the income from their assets (think deposits paying 4%).

The BTFP allows a bank to take its assets that lost value in the wake of interest rate hikes and post them as collateral, as long as they’re eligible for purchase in Open Market Operations. The bank can then make a new loan at current (higher) market rates, but now it takes on the risk of this new loan too.

Let’s put some numbers into the narrative to concretize things.

Imagine a bank has an asset earning 3% - it can be a mortgage or any fixed rate loan. The bank also has a liability paying 4% which we’ll assume is deposits. In our example it doesn’t matter whether there’s $1 million in assets and liabilities or $100 million, just that they’re equal.

We can immediately see that the bank has negative cash flow: its average interest on liabilities exceeds its average interest on an equal amount of assets. Why wouldn’t the bank liquidate its asset? That would give it cash that could then be loaned at today’s higher interest rates.

Because no one would pay par for it, precisely because interest rates are higher. The bank can only entice a buyer to take the asset if it sells at a loss. In other words, this is just like SVB…

So, the bank goes hat in hand to the Fed, showing that it has a 3% asset in a world of 6% interest rates on similar loans. The bank posts its 3% asset as collateral, and the Fed gives it cash, while charging the bank interest for the loan, say 4%.

The bank has now doubled its liabilities (all at 4%), while it still has an asset paying 3%, but now it also has a cash asset: the money lent by the Fed.

As fast as it can, the bank loans out this cash at the going rate of 6%. Now, we have liabilities (deposits and loan from the Fed) averaging 4%, and an equal amount of assets (loans to bank customers) averaging 4.5%. The bank’s back in the black.

St. Jerome has saved the day.

Of course, this simplified example assumes away things like risk that complicate the problem for banks and make the margins much thinner than they appear. The Fed also charges 10 basis points above the overnight index swap rate, so banks pay a premium to use this facility.

What’s changed recently to turn the BTFP into an apparent cash cow for banks is that the interest rate the Fed charges on these loans has fallen below the interest rate on reserves.

Suddenly, our hypothetical example above becomes much closer to reality. On top of that, it opens a whole new door for banks that are not in financial straits to make money on this arbitrage.

Previously, this happened 3 other times last year, but it was a product of the Fed raising rates, which made it difficult for banks to take advantage of the rate differential. What’s different this time is that interest rates on reserves haven’t budged since July, so it’s open season on the BTFP.

Banks can theoretically post all of their devalued assets (hundreds of billions in aggregate) as collateral, then simply park their loans at the Fed as reserves, earning a cool 46 basis points on the interest rate spread, 100% risk free.

Or is it?

There may not be default risk, but there’s a huge opportunity cost in most instances. Instead of a 5.40% rate at the Fed, a bank can earn over 7% on mortgages with relatively low risk. Auto loans and then credit cards represent additional steps on the risk/reward ladder.

You also have default risk associated with the devalued assets themselves. While that may not be an issue with Treasuries, we already saw what rising interest rates can do to mispriced MBS in the late 2000s.

If a bank with a lousy balance sheet gets additional loans and then its collateralized asset goes belly up, it’s in real trouble.

Troubled banks, therefore, likely can’t take advantage of this arbitrage because the margin is just too thin. They need to not only make money on the loan to/from the Fed, but the profit needs to also exceed the losses on their higher interest rate liabilities.

Let’s go back to that simple example we used earlier. We start with the same 3% rate on the asset and 4% rate on the liability. The rate to borrow from the Fed is still 4%, but now the rate paid by the Fed for bank reserves is 4.5%.

The bank will have liabilities with an average interest rate of 4% and an equal amount of assets with an average interest rate of 3.75% - it’s still operating in the red.

Sure enough, when we look at bank reserves, there wasn’t a noticeable change in the 2023 trend when this arbitrage opportunity appeared, indicating banks are not taking advantage of it en masse.

(N.B.: The plunge last week in this chart is just the typical year-end drop)

But what about those banks that are not in financial straits that we mentioned earlier?

These are almost exclusively big banks like JP Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo, but probably not BoA, since the latter has admitted to $114 billions in unrealized losses and probably has the highest ratio of unrealized losses to total assets among the big banks.

With his ample cash reserve, Jamie Dimon can put those unrealized losses to work and increase his bank’s reserves at the Fed. A few basis points on a billion dollars are nothing to scoff at.

But doesn’t that tie up JP Morgan Chase’s position for the year term of the loan? Nope - because there are no prepayment penalties with the BTFP.

So, when another troubled regional bank goes under, Dimon can simply cash out his chips but keep the money earned from the arbitrage, adding it to his massive cash reserve to buy that distressed bank…

If this is so obvious, why isn’t the Fed doing anything about it? Because they want it to continue.

As long as the BTFP rate is below the IOR rate, the program is supercharged in terms of its ability to inject liquidity into the banking system, which is the whole reason the Fed created it in the first place.

At first, it only made sense for a bank to use the BTFP if its balance sheet was so underwater that it felt like Ted Kennedy drove the bank home. Now, banks with enough cash on hand to ride out their unrealized losses can turn them into gains while they wait to gobble up a smaller fish.

That’s not a workable strategy for distressed banks since they need a better rate of return than they can get parking reserves at the Fed, even though the BTFP rate has come down.

That’s because what’s brought the BTFP rate down is other market rates coming down first, meaning bank assets (loans) created today have lower rates, on average, than in November.

This is problematic because rates on loans have come down more than rates on deposits, which regional banks are still struggling to attract. The 50-or-so basis point spread at the Fed just isn’t enough for banks still loaded down with 2% loans.

So, while the BTFP hasn’t quite turned into a universal money-making machine for every institution with primary credit privileges at the Fed, it is growing its clientele - massively.

Remember that at the end of the day, the Fed doesn’t care how the crisis is “resolved,” just as long as there are no riots in the streets. If the bomb can be diffused by the three biggest banks swallowing everyone else, the Fed is happy to make that happen and supercharging the BTFP helps that along.

After all, Treasury Secretary man-hands Janet Yellen has explicitly said further “consolidation” in the banking sector would be a good thing. Maybe it’s all “part of the plan…”

Never shut it off……Just changed some letters around and made a new Package like BTFB ETC…..

The second to last paragraph is very important to keep in mind. The fed does not care about you or the country, only that you stay home, work your depressing job at a desk, and be a good little servant.