The Banking Crisis is not Behind Us

The banking crisis is not behind us. In fact, the worst is yet to come. Last week’s H.8 data from the Fed showed bank deposits fleeing the system again, especially regional banks which had the fastest outflow since the panicked month of March. Neither the Fed nor Treasury seem to understand that their emergency measures have solved nothing, and only temporarily put off additional pain.

First, how did we get here? When Congress and the White House went on a three-year spending spree, the Treasury had to borrow trillions. But there wasn’t enough savings to buy all that debt, so the Fed created the money by buying bonds from existing bondholders, thereby freeing up whatever liquidity was tied up in old bonds. Awash with cash, everyone gobbled up low-rate securities – especially banks.

To help convince the financial system that the good times would last forever, Powell & Co. promised that inflation was transitory and interest rates would not rise for years. Both were lies. What’s more nefarious is that the Fed knew it had an inflation problem all the way back in March 2021.

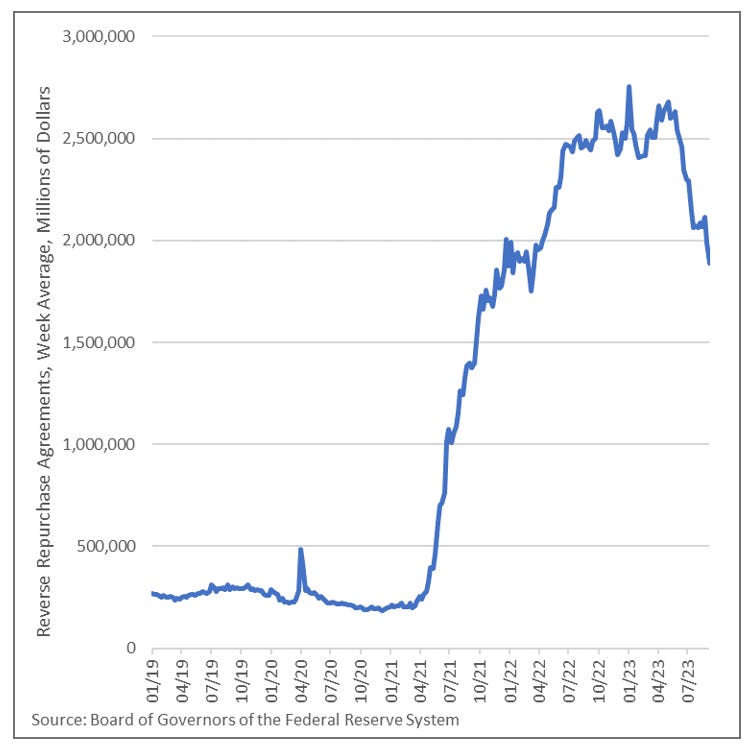

That’s when the New York Fed’s reverse repurchase agreements (reverse repos) had to go parabolic because of the severe mismatch between the Fed’s gargantuan balance sheet and interest rates. Keep in mind that at this point, the annual increase in the CPI was only 2.6% but the Fed was already struggling to control interest rates – they knew the storm was coming.

But Powell would be up for renomination soon, and wasn’t going to jeopardize that by stopping purchases of Treasury securities, so he kept his printer in high gear and provided all the money the Biden administration wanted, promised there’d be no inflation, and said interest rates would be at zero for years.

Since reverse repos are how the Fed temporarily soaks up excess liquidity, they’re a way of measuring how “oversized” the balance sheet is. If the Fed needs to repetitively use these short-term loans to constantly keep $1 trillion out of the system, then the balance sheet is basically $1 trillion too big.

The goal is for both reverse repos and repos to be near zero, meaning the balance sheet and interest rates are aligned with one another. The use of repos (liquidity injection) means there’s a shortage of loanable funds while reverse repos (liquidity reduction) mean there’s a glut.

Today’s surplus is from an oversized balance sheet, which was $2 trillion too big for over a year and a half.

So, the Fed lied – that’s nothing new. But this time they infected the entire financial system with promises of perpetual low rates. By pushing rates so low for so long, the Fed also made it impossible to find any high-yield securities in the market, so investors and banks alike could only buy low-yield securities, and many didn’t bother acquiring interest rate hedges.

After the Fed broke their “transitory” promise, they promptly broke their zero-interest-rate promise too. As banks had to sell assets to raise money to pay depositors, the banks were selling at a loss because bond yields and prices are inversely related. The banks with interest rate hedges were fine, but those without hedges went into a death spiral.

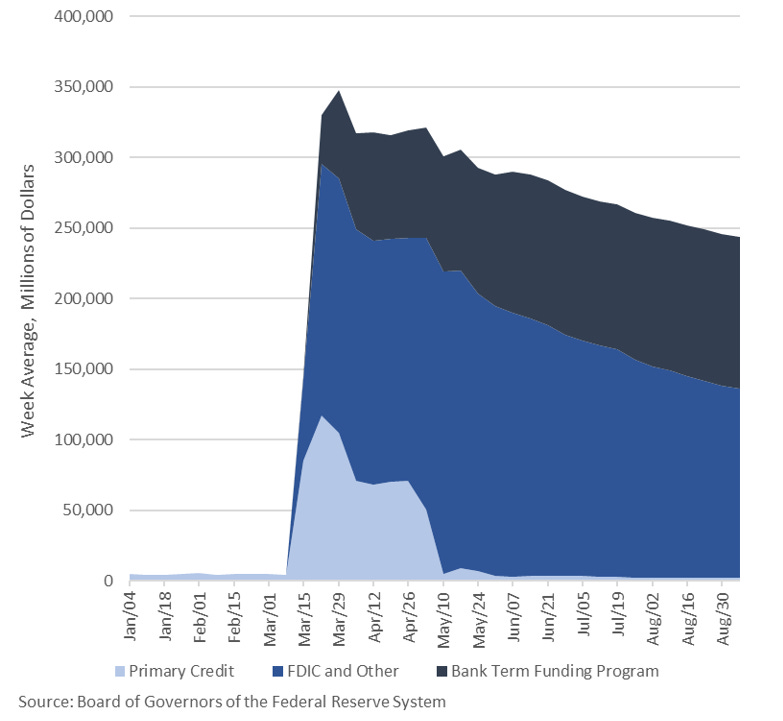

During one week in March, interbank lending collapse and the Fed wasn’t just the lender of last resort, but the only resort. Borrowing at the discount window set a record, and the Fed lent billions more through the FDIC. But the new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) immediately became a ticking time bomb.

The BTFP accepts devalued assets (remember those low-yield securities?) at par, allowing banks to borrow money they need immediately, but they must repay the Fed in a year because these are only 12-month loans. That means banks, especially the regionals, need to seriously clean up their balance sheets before the clock runs out.

When March 2024 rolls around, banks need to not only have enough cash to pay wary depositors, but they also need enough cash to repay the Fed so that they don’t have to sell any of their worthless bonds. Right now, the regionals only have enough to do one of these, but not both.

The banks who were smart and held interest rate hedges now have the cash to buy securities with relatively high interest rates. Even if the Fed adds a couple more 25-basis-point hikes between now and March, that won’t diminish the price of a 5% security very much.

But the regionals are cash-strapped – they used their BTFP loans to pay depositors, not improve their portfolios. Maturing securities are also being used to pay depositors, and the regional banks can’t afford new, higher-rate securities. When March rolls around, they’ll need to sell some of their portfolios to raise cash to repay the Fed’s loans. And they’ll be selling more worthless bonds.

In other words, the Fed didn’t solve the problem, but made it worse. Banks will be selling in March 2024 at even lower prices than they faced in March 2023.

There are three ways out of the next bank crisis. First, and most preferably, the government gets its grimy mitts out of the sector and lets the chips fall where they may. No more bailouts, no more random FDIC expansions to cover political donors, and no more emergency lending. Let the poorly managed banks fail and let the well-run institutions pick up the pieces. Preferable, but unlikely.

Option two is the most probable: the Fed and Treasury extend more emergency lending, coupled with more big banks swallowing up smaller failures, all while receiving taxpayer-guaranteed loans to finance the M&A activity.

Lastly, there’s a very unlikely preventative option. If all the securities collateralized by the BTFP (which just hit a new record) were T-bills, then there’s no problem, because their maximum term is 52 weeks. The problem with these securities was never default risk, but interest rate risk, meaning the security holder will get paid at maturity but they can’t sell it until then since no one wants a 1% return when a 5% return is available.

So, if the T-bills mature before the Fed’s emergency loans run out, then the mark-to-market losses are moot. The Treasury will simply pay the Fed (the current security holder) and then the banks don’t owe anything.

But the odds of this goldilocks scenario are insanely low. Much more likely is further government meddling in the financial sector, which is what got us into this mess in the first place.

Sign up to my free email list to get weekly posts on the economy and what’s really going in the world.

What a banger of an article to start with

Congrats