A View from 30,000 Feet

Take a step back, take a deep breath, and take a moment

Countless market “analysts” have weighed in over the last week, especially after the terrible jobs report, and we got every contradictory opinion under the sun. So, who’s right and who’s off their rocker? Everyone and no one.

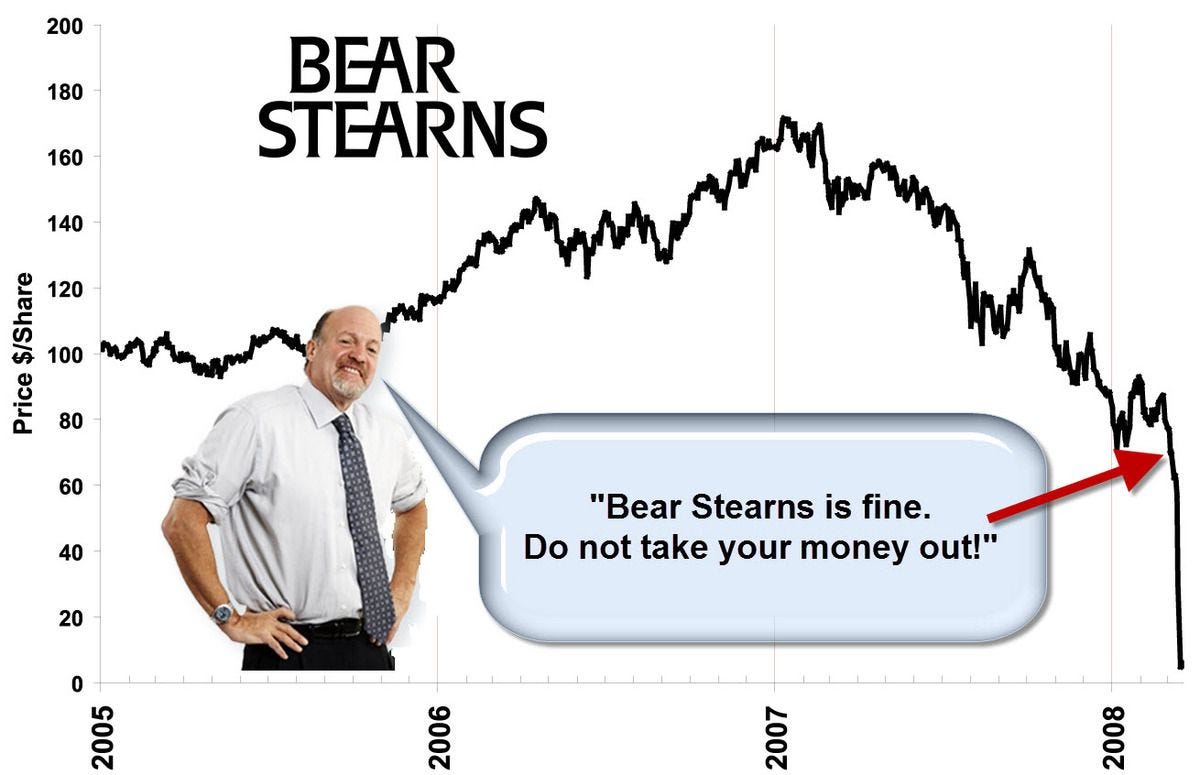

This is probably going to seem like a grab bag, but the wide-ranging topics you’re about to read have been arranged purposefully. It’s all part of an exercise to show the importance of a comprehensive view of the market and the broader economy. This is so that you don’t react like one of the talking heads yelling “buy, buy, buy,” or “sell, sell, sell!”

That kind of reaction stems from a myopic assessment of current conditions, zeroing in on just one thing and ignoring the other evidence all around you. There are a lot of moving parts right now and forgetting that fact risks ascribing everything to just one cause—a surefire way to get false positives and false negatives.

First up, let’s tackle that terrible jobs report from Friday, which allegedly was behind the market’s tailspin.

The unemployment rate in July rose to 4.3% and triggered the Sahm Rule, a recession indicator that has been astonishingly accurate in the post-war period. To be clear, this is not a predictive tool that has been around a long time; it’s just a few years old.

The author discovered a link between specific changes in the unemployment rate over time, and the timing of recessions. In other words, she found a pattern in the data that thus far has held true but may not do so in the future. Correlation does not mean causation, bla, bla, bla…

We discussed previously that lots of indicators point to recession today. And yet, this may not be one of them. The Texas hurricane in July caused disruptions that will eventually sort themselves out, and relatively quickly. The spike in unemployment claims from that state will evaporate in the coming months. Some of July’s increase in unemployment, therefore, was not due to structural problems in the economy.

This means the Sahm Rule trigger might be “artificial” for July. Nevertheless, the broader labor market trends are going in the wrong direction. As market participants slowly realize what we’ve been saying here for months, they’re starting to panic.

But there’s more than just panic selling going down on Wall Street these days. We’re also witnessing the unraveling of the Yen carry trade.

Carry trades are a way to pick up dimes in front of a steamroller - it’s perfectly safe, provided you keep pace with that steamroller. This arbitrage takes advantage of artificially low interest rates in one place, borrowing there and investing the principal somewhere else at a higher rate.

When central banks are keeping rates too low, looking at you Bank of Japan, then institutions can borrow Yen and invest their borrowed funds in the US, boosting demand for, and therefore the price of, equities.

But if the Yen appreciates relative to the dollar, it all falls apart. The steamroller suddenly surges forward, and that shiny dime you were picking up becomes a death trap.

Borrowing gives you an asset (cash), but it also gives you a liability (debt). Unless you leave that cash exactly as it is and stay purely liquid, borrowing will always mean leverage—and that means risk.

With the Yen carry trade, we’re talking about $20 trillion worth of risk.

If investors think a recession is around the corner, that means they’re anticipating both interest rates and equities in the US will decline. If returns on US investment fall sufficiently, then the math behind the carry trade doesn’t pencil out anymore, especially when the Bank of Japan just lifted its interest rate off zero for the first time in ages (rates were negative for years), as they attempt to arrest their currency’s slide against the dollar.

The result, as has been anticipated by more astute traders, is a violent realignment of investment. Yen-denominated debt is starting to be repaid via the sale of US assets, something that will likely continue for a while.

And speaking of those assets, the sell offs from last week don’t entirely jive with the inflation narrative. If everyone’s suddenly pricing in 100bps of cuts to the Fed Funds rate before year’s end, why would hard assets sell off? Those should be hitting new highs.

Let’s jump in our time machine for the answer: 1901.

The Northern Pacific Railway corner was the bloodiest financial draw in American history, with high casualties among not only its two main participants, but also the entire stock market. As J. Pierpont Morgan and Jacob Schiff vied for control of the road, with Morgan brokers buying shares at literally any price, Northern Pacific veritably levitated.

The stock zoomed up more than 100 points on a single trade. Investors smelled blood in the water, not realizing it was their own. Thinking the price a wild overvaluation, countless investors shorted the stock, then awaited the crash that must surely come. Unbeknownst to them, Pierpont would not be stopped.

With the price not coming down, but only going higher, the shorts suddenly found themselves desperate to buy up shares to cover their positions. For those who were severely leveraged, the short squeeze meant that paying virtually any price, no matter how catastrophically high, was better than returning to their brokers without cash to settle their positions.

Even at extortionate rates, call money dried up completely, so the only thing investors could do was sell everything else they had to raise cash for buying Northern Pacific shares. The entire stock market crashed — everyone wanted those Northern Pacific shares, and no one wanted anything else.

Fastforward to today, and the same principle is at work, though the magnitude is entirely different.

Major investment houses not only are getting out of the Yen carry trade but are also covering positions in cyclical stocks. They also want to be more liquid, anticipating further market declines and buying positions ahead — Berkshire Hathaway is now sitting on a record amount of cash, and Warren Buffet has a pretty good record of calling market peaks.

But for many market participants, raising a lot of cash quick to cover their bad positions often means liquidating their sounder ones, especially when leverage is involved. That’s why assets like gold got hit so hard, at least temporarily.

The yellow metal initially rallied on the lousy jobs numbers Friday, then tanked $60, before recovering about half its lost ground.

This is all combining to create a crescendo of irony. With the increasingly widespread belief of hard and fast rate cuts at the next meeting (some “analysts” are already pricing an emergency meeting rate cut, and no, we’re not kidding), bond yields are dropping.

That’s ironic because high Treasury yields are the Fed’s real motivation to cut interest rates; Powell needs to keep Yellen happy because the Fed is basically a captive of the Treasury at this point. But, if panicked market participants cause demand for Treasuries to surge and thereby push down yields, they’ve inadvertently done the dirty work for Powell.

As you see, there’s a lot going on here, and we certainly haven’t covered everything that was moving markets on Friday, let alone the whole week. Instead, what we hope you glean from this post is the realization that many factors are moving markets all at once, and sometimes they push or pull in opposite directions.

That can give confusing signals which are hard to interpret, but at least it gives you more time to react. The really scary days are when all the underlying factors move markets in the same direction, violently, and then you’re just along for the ride, hoping you prepared your portfolio in advance because it’s too late to react now.