Why Are the Inflation Numbers Fake?

A little hedonic adjustment goes a long way

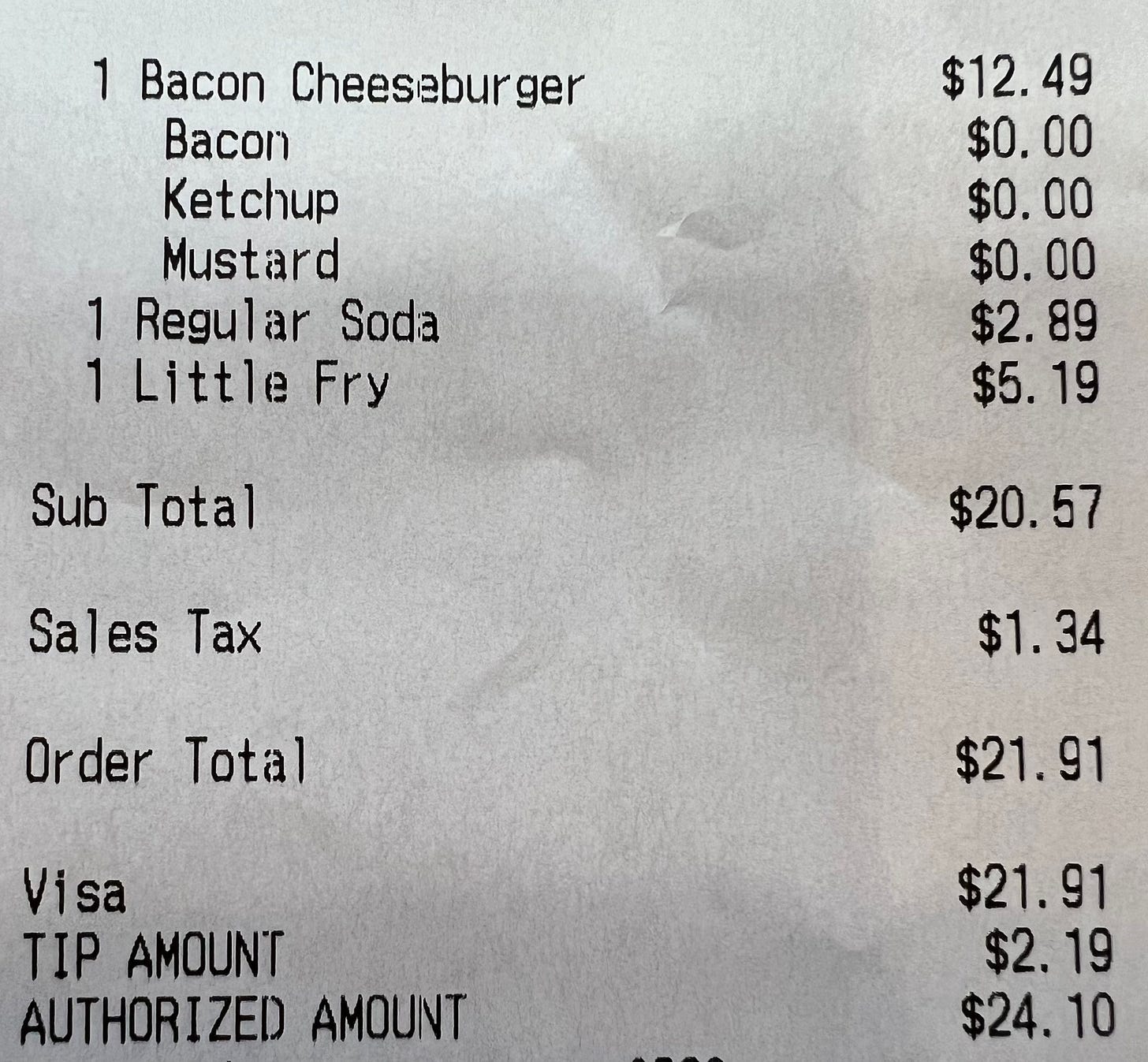

Earlier this year, an X post by our friend, Wall Street Silver, went viral and garnered over 25.5 million views. It was a Five Guys receipt for one burger, a small fry, and a soda—for over $24. That’s a Benjamin for 4 people…

This set off a cascade of people posting similar receipts, a trend that continues to this day. The latest twist is showing both a receipt from today and one from three, four, or five years ago—and what a difference!

Families are complaining on social media (and IRL) about food bills having doubled or tripled in a relatively short period of time. Plenty of fast-food prices have doubled in the last five years, and that data is widely available and indisputable.

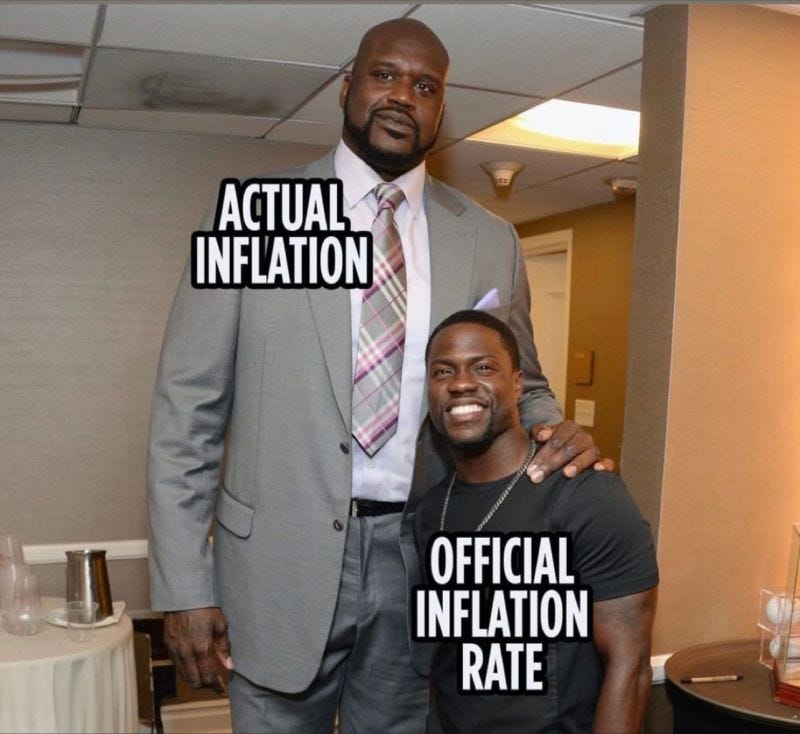

So, how is it that “official” inflation, especially for food, can be way less than people’s experience at grocery stores, or fast-food places, or even wholesale clubs?

Another friend of ours, Peter St. Onge, Ph.D., has frequently talked about the “Big Mac index” regarding prices and the true pace of inflation. The Big Mac at McDonalds is a surprisingly good inflation indicator because it has so many inputs.

Yes, it’s food (at least in theory), but it contains a wide array of foods (or food-like lab byproducts) including beef, grains, a couple of vegetables, a variety of plant-based oils, cheese, etc.

But it also includes labor costs. And fuel costs to cook the patties. And a different fuel to power the trucks that transport the ingredients. It also includes utility costs to keep the McDonalds open. Don’t forget the wrapper and bag your sandwich comes in. And so on.

In short, there are a surprising number of input costs for a Big Mac. If you make it a meal instead of just the sandwich, it expands the number of inputs even further and branches out to some surprising industries.

So, that artery-clogging, delicious meal is a decent measure of the dollar’s buying power — or lack thereof.

How does the Big Mac index compare to the most common inflation metric, the consumer price index? The latest annual CPI reading is 3.0% while the same time period for the Big Mac index shows an increase over 8% — more than twice the “official” rate.

But how on earth do we get such disparities in these readings? One explanation is that many components of the CPI are plummeting in price, canceling out the other items that are rising. When we look at trimmed-mean and median CPI, however, we can see this isn’t the case.

We also know this isn’t the case from our own personal experiences as well as survey data and proprietary price indexes.

That’s not to say some prices haven’t fallen since the middle of 2022. Gas is not quite as expensive, for instance, though still much higher than four or five years ago.

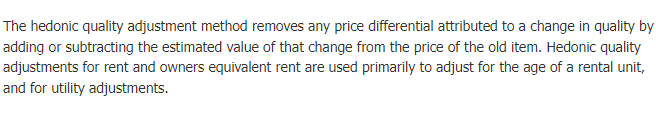

Ok, so we’re back at square one. How can CPI be understating inflation so much? A lot of it has to do with what you might call the statistician’s version of quality control: hedonic adjustments.

This is basically how a tool like the CPI tries to account for changes in quality over time. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, which compiles the CPI, has the following on their website:

To a certain extent such an adjustment makes sense. Think about how much cars and light trucks have improved in the last 30 years — comparing the 1994 and 2024 model years is apples and oranges.

Cassette and CD players have been replaced by Bluetooth. There are airbags everywhere. Fuel efficiency is better. Four-speed automatic transmissions have given way to 6-, 8-, and 10-speeds. There are back-up cameras, blind spot monitors, and just about everything is heated including seats, steering wheels, mirrors, and wiper blades.

What the hedonic adjustment is supposed to do is control for this higher quality. If the car is conceptually twice as good, you’d expect the price to double, but we don’t want to capture that in the price index. Instead, we only want the price index to increase when the same product or service becomes more expensive.

That’s because we’re trying to measure the same thing over time, not measure different things over time. The obvious problem is that things don’t stay the same over time, hence the need for this adjustment.

But, like all things that the government touches, this one has also been ruined. The whole point of the CPI and similar indexes is not to measure the true cost of living — that’s just the window dressing for the bureaucrats and their bean counters.

Instead, these prices indexes are designed to minimize the true increase in prices. The hedonic adjustment is part of that methodology.

In short, dubious quality improvements are grossly overestimated, effectively erasing many price increases. A great example of this is regulation.

When the government regulated clothes washers and drastically reduced the amount of water they could use, manufacturers had to make radical changes to the machines’ designs, and by almost all counts, the products became worse.

Yes, they used less water. But they also created much more friction during washing and wore out clothes faster. Clothes also tangled more, reducing how well they got cleaned. Standard detergents didn’t work properly with so little water, so new ones had to be used, but these were good food sources for molds and mildews. Consequently, clothes begin smelling if left in the washer for just an hour or two.

The washing machines themselves build up a residue from modern detergents which harbors bacteria, requiring the cleaning machine to itself need cleaning. This is why clothes washers today have their own cleaning cycle which requires a special detergent. To top it off, consumers report frequently needing to wash clothes multiple times in order to really get clothes clean. That reduces the water savings of today’s more “efficient” models, but it also can result in a net negative savings on electricity.

You find the exact same complaint on dishwashers. Many people have to prewash everything by hand because a lot of modern dishwashers just don’t work well. It’s not really the manufacturer’s fault — it’s illegal for them to build a model that uses enough water to clean your dishes.

So, here’s the crazy thing: the same regulations that make modern appliances useless and more expensive, are also cited as an improvement in quality for hedonic adjustments.

Yeah, you read that right — if regulation makes something more expensive, then government-paid statisticians assume the quality improved.

It’s difficult to overstate how insane this is. Government mandates simultaneously made your appliances worse and more expensive, but the hedonic adjustments zeroed that out.

That’s true for literally any additional costs imposed by regulation. If the government forces a manufacturer or service provider to do something, the government-paid statisticians grab their erasers and wipe that cost increase off the books.

An economist who teaches at the University of Chicago recently estimated that excessive regulation under the current administration in Washington was adding $5,000 per household, per year, in additional costs — all of which is excluded from the CPI.

We’re not trying to get political here; this is just an illustration of how “official” inflation metrics are total garbage. The median household is currently losing about 7% of its annual income to additional regulatory costs, and they’re trying to tell us inflation is only 3%.

We’re calling bull$#*! on that.

Great explanation. I find it funny that we're adjusting for increased "quality" when, experientially, it seems like the quality of many, many items is only going down (example: it's hard to find real wood furniture these days, even at "high end" stores). The washing machine was a great example. Do you think regulation is the main reason for all of these quality decreases we're seeing, or what other factors do you think are at play? (I definitely agree regulation is a huge one, just curious as to what other factors might be involved.)

I don't know why we let "official" stats cloud our eyes from seeing what's really going on right in front of us.

Well explained today, and the memes were fantastic :)