Making Sense of Macro Forecasts

How Three Fed Banks Produce Wildly Different Results

The best-known GDP predictions among regional Federal Reserve banks are from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Throughout each quarter, they frequently update their nowcast with the latest economic data and have proven to be a fairly reliable gauge.

But they’re not alone - the Federal Reserve Banks of New York and St. Louis also produce nowcast estimates, and the three can vary considerably. Understanding why that is can help the individual forecaster or investor understand which direction the economy is headed.

First, what’s a “nowcast” anyway? It’s basically a forecast that’s updated in real time with newly released data. Nowcasts rely heavily (or exclusively) on very recent data, as opposed to long-term trends. Similarly, they don’t look that far into the future—usually just a quarter or two, tops.

With such narrow and similar scopes, the primary difference between these three Fed bank forecasts is the data they include in their algorithms and the weights they assign.

The Atlanta Fed arguably relies the most on hard data—like how much consumers are actually spending and how much prices are increasing. The St. Louis Fed, on the other hand, relies much more on soft data—like how consumers perceive the economy and inflation expectations.

You can make both empirical and theoretical arguments for either of those two weighting systems. There are times when hard data line up much better with the advance GDP report, while other times the soft data end of being more accurate.

Just determining which of those two times you’re in right now is a whole predictive science in and of itself.

On the theoretical side, hard data tend to be backwards-looking while soft-data leans toward being forward-looking. However, people’s perceptions are often incorrect, like when the vast majority of folks in 2005 thought the housing bubble would go on forever—how wrong they were.

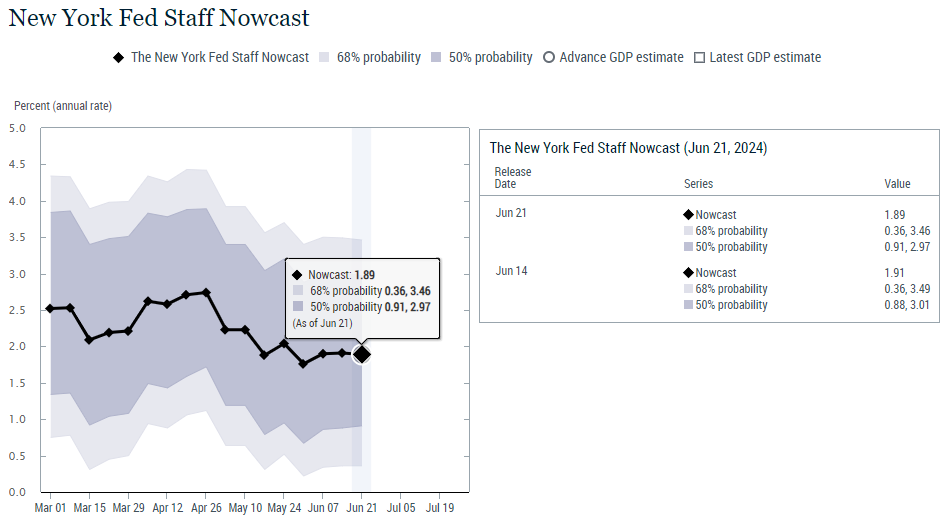

The New York Fed arguably has the best balance between the two, in terms of weighting hard and soft data. That doesn’t mean it’s the most accurate, however. It’s like a well-diversified investor who never gets the highest rate of return but isn’t the worst either.

Another thing to remember is that GDP is not always a good measure of the economy. As the expense side of the income equation, it really only tells us how much is being spent, not what is being purchased.

If you spend the same amount of money but buy things you value less, that marks a decline in quality of life. Likewise, if the government is inefficiently spending an increasing amount of the nation’s income, that’s a net-negative for consumers.

That adds to the confusion because the Fed banks aren’t exactly trying to estimate the size of the economy, but a specific metric, one which is subject to its own flaws.

Nevertheless, the Fed banks have historically done pretty well for themselves when it comes to these nowcasts, being right up there with professional forecasters—it’s amazing what a bunch of Ph.D.’s can do when they’re not focused on “equity” …

Anyway, we mentioned that the St. Louis Fed relies disproportionately on soft data, and it’s no coincidence that in the post-covid world this nowcast has tended to lag way behind Atlanta and New York.

People feel lousy about the current economic climate and their expectations for future conditions aren’t pretty either. Those negative perceptions have been in stark contrast to seemingly positive hard data.

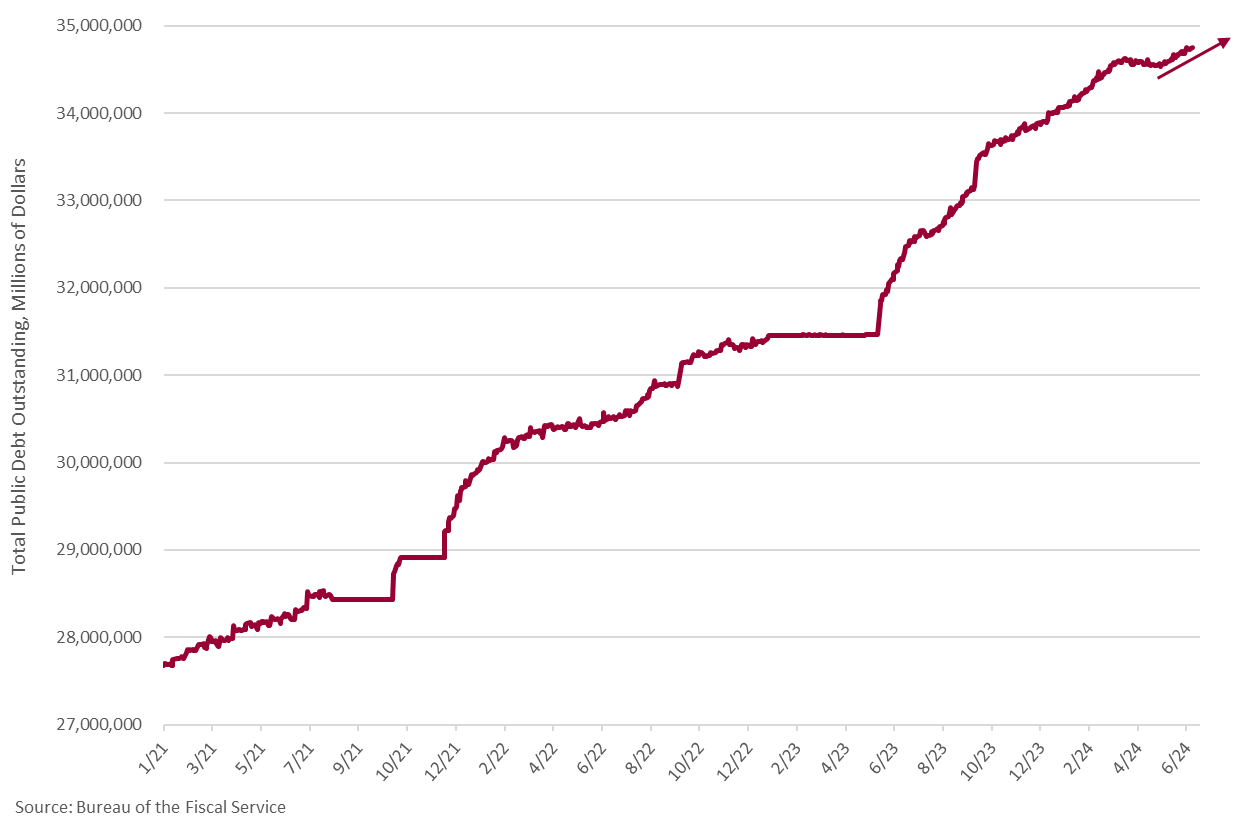

A key reason for this divergence has been debt accumulation. Consumers and government alike have been on a debt-binge for the better part of four years, with the increase in the federal debt accounting for all of recent GDP “growth.”

Essentially, the federal government is “buying” positive GDP numbers by pulling forward what would have been future growth to today. In this way, they’re putting off any chance of a recession.

Remember, a country can avoid a technical recession for a very long time if they’re willing to go into enough debt. The U.S. has been willing—and able.

Of course, avoiding a technical recession (two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth) is not synonymous with avoiding an economic downturn, especially when you’re considering how the average American is doing.

We’ve done multiply deep dives in lots of previous posts about how “official” economic metrics can look so good while people still feel bad about the economy—on everything from inflation, to growth, to jobs.

This discrepancy has made the St. Louis Fed’s nowcast a pretty consistent undershot of the advance GDP numbers because of the aforementioned reliance on soft data. Until the hard and soft data realign, expect this divorce to continue.

If it sounds like the Atlanta Fed has this pretty well wrapped up, there another very important set of assumptions to consider, and this has been the Atlanta Fed’s Achilles’ heel more than once.

A nowcast typically makes its initial prediction when the very first round of data becomes available. That’s problematic from the standpoint of the period being predicted isn’t even over yet.

When initial data became available for April, the month wasn’t even over yet, but the New York Fed had the Q2 nowcast up and running.

This brings up an interesting question that is illustrated in the current consumer spending numbers: what assumptions do you make about trends?

The only consumer spending numbers that we have right now for Q2 are the April consumer expenditures, and they were negative. Should a forecaster assume that the consumer spending growth from Q1 will remain? Or should you extrapolate from April’s data that the rest of Q2 will have negative growth in this category?

The Fed banks each treat this question differently. For the Atlanta Fed, their nowcast demonstrates a clear pattern: they assume historical growth trends to be the norm, and adjust their nowcast as new data come in.

When the data showing a downturn in consumer spending were released for April, the Atlanta Fed adjusted their nowcast down to account for this, but—and here’s the important part—they assume that growth will return for May and June.

Of course, as reports like retail sales come in, they’ll further adjust the nowcast, but the assumption that is baked into the cake is that historic norms will continue.

This approach makes a lot of sense from the standpoint of economic data being very noisy. It’s not uncommon that one of three months in an overall strong quarter will have a downturn. But this makes it easy to miss inflection points.

Like everything in economics, there are tradeoffs to the methodologies between the different nowcasts at the regional Fed banks. We often argue for a comprehensive view of markets, and this is another area where it pays off.

Does the overall landscape point to a change in direction? Are the economic winds no longer at your back, but in your face? Is there agreement with how people feel about the economy and the size of their bank accounts? And what can they actually buy with those bank accounts?

Let’s go back to the Atlanta Fed’s model for a concrete example. Between pessimistic consumer attitudes and consumer credit hitting a wall, it looks like the negative growth in consumer expenditures for April was not an aberration, but possibly the start of a new trend.

That means the assumption of a return to robust consumer spending growth is misguided. Since this category of spending makes up somewhere between two-thirds and three-quarters of GDP, this is a huge datum point.

Negative consumer spending growth is often all it takes to push overall GDP growth into the red.

That’s why both the New York and St. Louis Fed nowcasts, which have lighter assumptions about historic growth rates continuing, are indicating much lower growth than the Atlanta Fed.

If you’re trying to figure out what direction the economy is heading, you don’t necessarily have to reinvent the wheel when it comes to forecasting. If you just understand how other forecasts work, you can decide if those numbers are good predictors, given whatever today’s unique circumstances are.

Was April merely a speedbump for the consumer? Then the Atlanta Fed’s assumptions, and therefore their nowcast, are more likely to be accurate.

Was April merely a foretaste of a much rougher road ahead, with the hard data finally catching up to the soft data? Then the Atlanta Fed is woefully overshooting.

Knowing how these nowcasts are constructed is key to both knowing why they can diverge so much, and knowing when to trust one, and distrust another.

Summarize: Junk In Junk Out.