Higher Inflation or Higher Interest Rates?

A key component of the financial system's plumbing is sending a warning

It’s time to return to one of our favorite pieces of financial plumbing: the repurchase agreement market, or repo market for short. What seems like a relatively small and innocuous series of exchanges between financial firms and the Federal Reserve is actually a treasure trove of information. So, what’s it telling us now?

First, a recap. There are two sides to the repo market, and they work exactly the opposite of one another. On the one side are repos which are a way for the Fed to inject liquidity on a very short-term basis, as in an overnight loan.

It works like this: the Fed offers to loan money for 24 hours at a specific interest rate. When you repay the loan tomorrow, you give your regional Fed bank the principal plus the interest. The loan is collateralized (typically with treasury bonds) to ensure repayment.

Thus, while repos allow the Fed to very quickly add tremendous amounts of liquidity, that liquidity is then subtracted back out of the financial system the next day. To keep the liquidity infusion going, Fed banks (chiefly the New York Fed) would need to continuously, day after day, make these short-term loans.

Of course, that’s an expensive way for financial firms to increase liquidity over the long term. They’d typically rather sell an asset to the Fed and get cash that way because it doesn’t involve paying any interest.

And that’s exactly what happens when the Fed conducts open market operations and buys bonds. Now the Fed gives exchanges money it created out of nothing for bonds held in the private market. Unlike repos, this is a permanent exchange.

And that’s where repos get their name—the asset is not just purchased but then it’s also repurchased at a specified future date. Historically, the market was constantly tapping this rep facility at the Fed for a relatively low volume of loans, but that all changed with the global financial crisis and the institution of ZIRP (zero-interest-rate policy)…

When the mortgage meltdown was in full swing in 2008, leverage once again became a dirty word as the financial house of cards built on subprime mortgages came crashing down. Loans out of the repo facility quadrupled as everyone turned to the “lender of last resort.”

Eventually, the Fed bought so many bonds and then mortgage-backed securities that the money supply exploded, and firms were awash in liquidity. The repo facility basically went from record usage to nothing in a year because of open market operations that forced interest rates to zero.

That situation remained until the Fall of 2019 when the Fed overtightened by selling off too much of its balance sheet and the central bank briefly lost control of interest rates, with overnight rates zooming higher. Desperate for liquidity, banks turned to the repo facility for volumes of cash twice as high as the record set a decade prior.

By the start of 2020, the Fed had added sufficient liquidity through open market operations the repo usage was plummeting back down, having fallen more than $100 billion.

But then the government shut down the economy in March. Repos went up like a rocket.

Unlike in the global financial crisis or the Fall of 2019, the Fed pulled out all the stops in the Spring of 2020 and bought literally everything in sight. In little more than three months, the repo facility went from almost $450 billion to nothing and stayed there for three years.

That’s when the Fed created a regional bank crisis and financial firms were once again desperate for short-term cash infusions. Repos spiked, but only briefly and the magnitude was relatively small because the Fed created a whole new lending facility for anyone who got on the wrong side of the interest rate trade—it was another bailout.

So, what do these repo volumes tell us? What way to interpret them is as a measure of the relative size of the Fed’s balance sheet, given the Fed’s interest rate target range and the relative quantities of demand and supply of loanable funds. Let’s illustrate this to make it clearer.

When the government shut down the economy, lots of people panicked, including the government. People were hoarding cash and didn’t want to lend any money in the form of buying bonds, at precisely the same time the government was trying to sell trillions of dollars in new bonds. The supply of loanable funds fell, and the demand rose.

Econ 101 tells us that this results in a higher price. In the loanable funds market, the price is the interest rate. When the prevailing market interest rate for short-term loans exceeded the interest rate offered by the Fed on repos, everyone surged into the latter trade.

That explains a very important function of repos: they’re a way for the Fed to maintain a ceiling on interest rates. Given market conditions, an increased use of the repo facility means the Fed’s balance sheet is too small. Alternatively, the interest rate set by the Fed is too low, given the balance sheet’s size.

Let’s stick with the first interpretation in this example. As the Fed went on its biggest buying spree ever, it doubled the balance sheet to almost $9 trillion. With such ample liquidity, there was no difficulty in maintaining a ceiling on interest rates, so repo usage evaporated.

The balance sheet was no longer too small relative to market conditions. Unfortunately, now it was too big. Enter the reverse repurchase agreement, reverse repo.

These work exactly the opposite of a repo. In its simplest form, you lend the Fed cash, and you receive a Treasury bond as collateral. Tomorrow, the Fed gives you back your cash with interest, and you return the collateral to the Fed.

Unlike repos, this immediately raises a question: why on earth would the Fed need a loan? They have a money printer for crying out loud. This is where it helps to understand repos before diving into reverse repos.

Just as repos allow the Fed to inject liquidity and put downward pressure on interest rates (maintain an interest rate ceiling), reverse repos allow the Fed to soak up liquidity and put upward pressure on interest rates (maintain an interest rate floor).

Thus, the reason for the reverse repo facility is not because the Fed is desperate for cash. Rather, the Fed is desperate to get cash out of the financial system and can’t fine tune things quickly enough with open market operations.

Historically, reverse repos stayed at a relatively low level, just like their repo counterparts. However, after the institution of ZIRP and multiple rounds of quantitative easing, the Fed had to start mopping up liquidity constantly to avoid setting off runaway inflation. It turned to the reverse repo facility.

The reasoning behind using reverse repos to absorb liquidity while quantitative easing simultaneously added liquidity was to create money for the Treasury to spend (hence buying Treasury bonds) but prevent that newly created money from multiplying in the banking system.

We’ve covered this mechanism in detail in earlier posts, but the quick and dirty version is that banks can’t lend to the private sector if they’re too busy lending to the Fed through the reverse repo facility.

By absorbing excess liquidity, the Fed maintains an interest rate floor and the volume of reverse repos tells us how hard the Fed is having to work to maintain that floor. By late 2022 and into 2023, the Fed was working overtime.

Reverse repos across the regional reserve banks exceeded $2.5 trillion. That implies the Fed’s balance sheet was roughly that oversized, given the interest rate target range at the time and the relative supply and demand for loanable funds.

So, why did reverse repos drop like a rock after the Spring of 2023? Two reasons.

First, the Fed was selling off its balance sheet and drawing liquidity out of the system with that mechanism, so less liquidity needed to be absorbed by the reverse repo facility. Second, the demand for loanable funds was entering the stratosphere as the federal government continued running multi-trillion-dollar deficits.

That meant the demand for loanable funds was rising while the supply was falling. Going back to Econ 101, that means the price—the interest rate—will rise. With the market interest rate rising, the Fed was no longer struggling to maintain an interest rate floor and reverse repos came back down to earth.

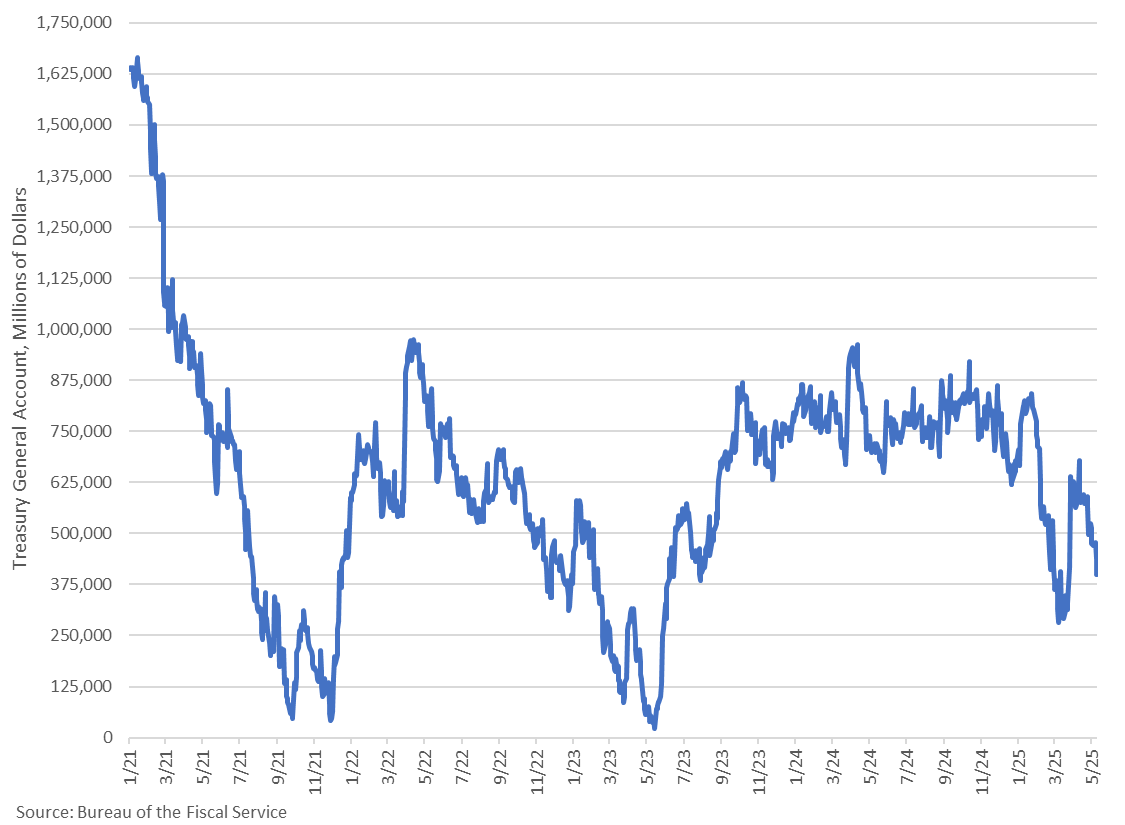

But reverse repos should’ve gone to zero by now, so why haven’t they? They’re still over $500 billion, implying the balance sheet is still significantly oversized, even after the misguided rate cuts of Fall 2024. Here’s what’s going on.

Number one is that most reverse repos aren’t even coming from the U.S. anymore—they’re foreign accounts. Because financial firms and central banks around the world have slightly decreased their use of the dollar as a reserve, those foreign entities are looking for a depository for this extra cash. The reverse repo facility is a perfect fit, especially since it' provides a risk-free rate of return.

The other component is the debt ceiling, which has been in effect since the start of the year. Because the Treasury can do no net borrowing (only roll over maturing debt), the demand for loanable funds has gone way down as Treasury just burns through its cash on hand.

The icing on the cake is that the Fed cut 100 basis points around the November election but is still running off Treasury securities, albeit at an anemic pace, and mortgage-backed securities.

We can interpret the data as follows:

The reduction in demand for loanable funds is temporary. Once the debt ceiling is lifted, the Treasury will borrow between $500 billion and $900 billion immediately, mostly in T-bills, which should completely drain the entirety of the reverse repo facility since T-bills are frequently traded like cash (low liquidity penalty).

After this, the repo facility will kick back into gear as the Fed switches from absorbing to adding liquidity. Possibly in a single day or maybe two, the secured overnight financing rate will swing from the lower bound of the Fed’s target range to the upper bound.

That will make the Fed uncomfortable, and likely prompt one of two reactions.

Option one is to stop the balance sheet runoff, at least for Treasuries, and then resume buying them shortly thereafter.

Option two is to let interest rates rise and maintain the slow pace of the runoff.

So, it’s a choice between higher inflation rates or higher interest rates. Those are our only options. It’s not pretty, but if you know what’s coming you can at least protect yourself financially…

Central banks cause more problems than any they pretend to solve. Let the markets set the interest rates. It couldn't be any worse and at least would be real world instead of wonks sitting around pretending they can totally understand the whole US economy and what interest rates, etc. are needed. Time to end the Fed.