A Divining Rod and 2 Crystal Balls

What markets are telling us about the direction of the economy and how to invest

Wall Street has been throwing up confusing price signals for weeks now. Since the Federal Reserve announced an emergency-sized cut of 50 basis points in the Fed Funds rate, we’ve seen consumer and sovereign debt interest rates rise.

Yields on Treasuries went up, not down. Same thing with the average rate on credit cards. And mortgages. It’s the opposite of what you’d expect.

But the Alice-in-Wonderland feelings don’t stop there.

Equities and fixed income are supposed to move in opposite directions. They’re not. Instead, both are rising, with a rally in stocks and bonds happening at the same time.

Oh, and don’t forget the housing market. We detailed in a previous post how home prices and interest rates became decoupled in the last couple years, creating this phenomenon where home prices went up as interest rates went up—normally, they move in opposite directions. We also explained that they were recoupling.

As interest rates on mortgages declined over the last several months, it didn’t bring down home prices as many had hoped. Instead, it led to another rally, sending home prices to new record highs. Are those higher home prices resulting in the anticipated increase in supply? Nope.

And what about manufacturing? The sector is still mired in recession and has been for two years. There is still a steady stream of layoffs and although the employment losses aren’t catastrophically large, they add up to more than 140,000 since January 2023. So why are investment managers suddenly so bullish on manufacturers?

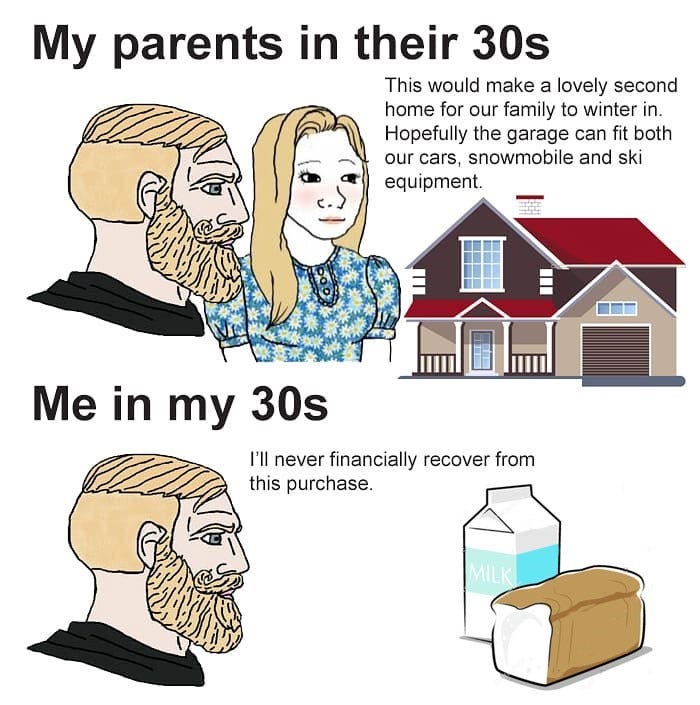

Honestly, why be bullish in general? Many of the earnings beats that we’ve been seeing are really misses based on original forecasts. The “beats” were essentially created by published new forecasts with huge downward revisions.

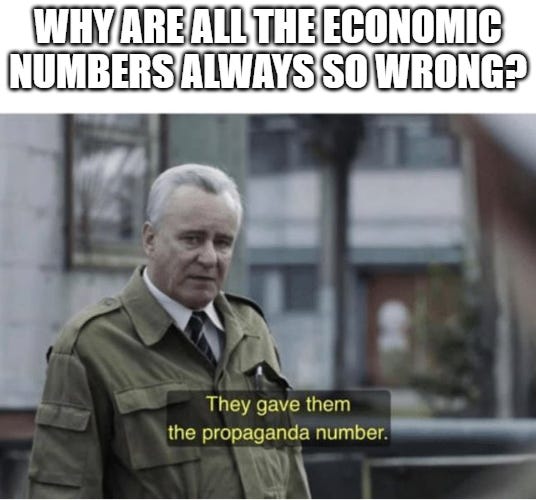

That mirrors, in many ways, the revised economic data we’ve been getting from the government bean counters. It’s a great number at first—beating expectations—but then it’s revised down, and no one bothers to notice that the final revision is actually a miss from the original Wall Street consensus.

Instead of 11 job estimate beats in 12 months, the Bureau of Labor Statistics really delivered 7 misses for nonfarm payrolls.

Conversely, when things like gross domestic income were revised up recently, it wasn’t done because of better data, but simply a tweak to the models at the Bureau of Economic Analysis, resulting in hundreds of billions of dollars in savings appearing out of thin air.

And that’s despite Americans saying in poll after poll that they have no savings left. Their bank accounts have run dry, and their credit card balances have ballooned. Last week’s post dealt with some of the reasons why our official economic data is turning into junk, but that doesn’t explain the mysterious market pricing we’ve been seeing.

We return to the question of why equities and fixed income are both rallying. Let’s say the official government data were showing absolutely no growth and very high rates of inflation; we should then see that reflected in the market. Or, if no one believed the official data anymore, we should see that reflected too. What makes current market moves so confusing is that equities and fixed income seem to be reacting to different data entirely.

Furthermore, markets have reacted in a nearly identical way to projections of seven rate cuts as they did to projections of just one cut. To Wall Street, a cumulative reduction of rates by 350 basis points seemed indistinguishable from a reduction of 50.

For a while there, it was pretty clear that good news was bad news, and bad news was good news. In other words, any data pointing to sour economic growth—like a lousy jobs report—was supposed to be the green light for the Keynesians at the Fed to cut rates hard and fast. Conversely, strong jobs numbers were supposedly the Keynesians’ red flag indicating more inflation and rate hikes to compensate.

Regardless of how flawed this thinking was, what followed was a predictable market reaction. The prospect of rate cuts made people anticipate cheaper borrowing costs. That sent equities soaring and drove down yields on fixed income, like bonds.

Fast forward to today, and even this formerly rock-solid relationship has broken down. Analysts find themselves at a loss regarding how to square the circle of these inexplicable market moves.

It seems there are only two explanations that fit the equity and fixed income data, and only one of those theories also aligns with movements in the barbaric metal.