16 Tons of Consumer Debt

I owe my soul to the company store...

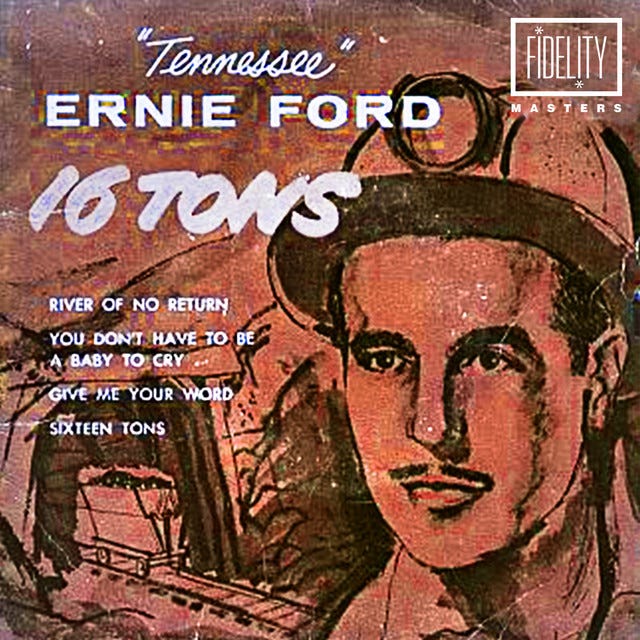

There’s an old folk song from the 1940s about the hard lives of coal miners, particularly their finances. Sixteen Tons describes how these laborers did their back-breaking work, only to fall deeper into debt. But don’t think this is a thing of the past because consumers today have fallen into the same trap—so much so that South Park even used the song in an episode not that long ago…

New data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shows household debt in the second quarter set yet another record high, now at $17.80 trillion. Of that, a record $1.14 trillion is credit card debt. For the first time ever, Americans are paying over $300 billion annually in credit card interest.

Note that this is just the finance charges, not a dime towards principal. Remember that these folks racked up debt because they couldn’t make it from paycheck to paycheck. They were using credit cards to finance groceries, gas, and rent.

At least two finance companies have popped up in the last few years that only let you purchase food. In other words, these firms offer lines of credit that can only be used at grocery stores. That’s how bad it is out there for the average joe.

If people can’t afford the current cost of living, why would we think that they can afford interest payments on top of that? The consumer’s situation is shockingly like the federal government’s.

Unable to pay its current bills, the government finances the deficit, which increases the debt. The debt costs interest to service it. That interest must also be financed. That increases the deficit. That increases the debt. And so on…

At this point, consumer debt is snowballing faster than incomes are growing, in part because of today’s return to normalcy regarding interest rates. We as a society got used to artificially low rates near zero percent because that’s what prevailed for more than a generation.

Boomers may scoff at eight percent mortgage interest rates because they remember 20 percent rates in the early 1980s, but Millennials and Zoomers have never seen this before. They grew up in a world where leverage was the norm and debt was good.

Since the day they turned 18, their mailboxes were full of credit card offers with introductory rates of zero percent, and relatively low rates thereafter. Student loans at four percent? Yep, that was common too. Car loan at two percent? Sign me up.

The easy money fed a culture of instant gratification and encouraged everyone to lever up. So, they did.

This arguably reached its zenith in 2020, or perhaps 2021, when the world was so awash with cash that corporations were borrowing money to buy back their own stock, since the rate of return on annual dividends was more than the APR on available credit.

Even though consumers didn’t max out all their credit cards right away in those years (they were actually paying their balances down in 2020), people did greatly expand their lines of credit, typically by opening up more credit cards.

As the money-printing sugar high faded into the pancreatic attack of inflation, people turned to those credit cards in earnest. Balances started exploding.

Still, it could be worse. That massive debt load could be paired with punishingly high interest rates. As long as rates stay low, even large balances are relatively painless to finance.

Oh $#!+ …

Rates going from zero to normal was when consumer debt turned into a runaway freight train. Average weekly earnings growth is still so far behind inflation (lagging about 4 percent since the start of 2021) that there’s no room in most people’s budgets for these high financing costs. Instead, many folks are making only minimum payments while charging still more to their credit cards.

In other words, their balances are growing, which means next month’s interest will be even larger. It’s a debt death spiral for countless low- and middle-income American households—an entire generation didn’t even know interest rates like these were possible.

Even for those youngsters who did know about the 1970s and 80s, what they read probably seemed like ancient history, and they likely had on their minds the same words which have frequently been the last to escape the mouths of the slaughtered: “It cannot happen here.”

But happen it did. We are fast returning to a nation of debt slaves. The math seems hopeless, especially for young people. But it’s also bleak when you consider that interest on the federal debt is running at an annualized $1.2 trillion.

Where, then, is the hope? Well, we’ve been here before, at least on the consumer level, many times. Let’s go back to the folk song with which we started this post. It’s based on the lives of 19th century coalminers who toiled away in deadly conditions, and they weren’t even paid real money.

Instead, they were commonly paid in some kind of token that was accepted at the coalmine’s general store. Thus, their employer effectively forced them to return all wages paid.

But the general store, in a spirit of charity, would extend generous lines of credit to coalminers and their families, often at extortionate interest rates. Maybe the rate didn’t start out that way, but it got there eventually. (Sound familiar?)

The result was households quickly falling into debt and when the weekly pay was doled out, the entirety of it went to pay off interest and just some of the principal, so nothing was left after that. For the next seven days, the coalminer and his family had to keep using their line of credit at the store, just to survive.

After a lifetime of work, you’d die penniless—no exaggeration.

The vicious cycle wasn’t ended by labor unions, although that is a trope commonly printed in grade school history books. Rather than less competition, it was more competition that broke the cycle.

As more companies got licenses to dig, the number of coalmines expanded, and firms competed for workers by offering higher wages. Competition between coalmines for increased output and market share also led to development and implementation of new technologies which made workers much more efficient.

With more capital at their fingertips, workers were more productive and commanded higher wages. It didn’t happen overnight, but progress slowly ended the debtor’s prison of Appalachia.

Ironically, it was those areas that were most heavily unionized which had the token payment system and perpetual debt the longest. Just one reason for this was the mines that were forced to pay above-market wages invested less in machines and so their workers had less capital and were less productive.

Regardless, we need a similar productivity miracle to get the consumer out of this debt death spiral. Maybe that will come from AI, or maybe something else—but we better hope it gets here soon. Consumer spending is between two-thirds and three-quarters of the economy. The brakes are on hard for revolving credit growth, and that’s a bad omen for economic growth.

In closing, it’s worth quoting the refrain of Sixteen Tons in full:

You load sixteen tons,

And what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt.

St. Peter, don’t you call me ‘cause I can’t go;

I owe my soul to the company store.

I grew up in coal mining country in Southeastern Kentucky. In addition to keeping coal miners enslaved to Coal companies, Unions employed Luddite opposition to the much more efficient mining machinery that coal companies tried to introduce. Another revealing song that came out of the Appalachian experience was The Ballad of John Henry, wherein the hard working John Henry sought to compete with mechanical pile drivers in penetration rock. The audience for John Henry cheered him on even when the victory was obviously tilted toward the machine.